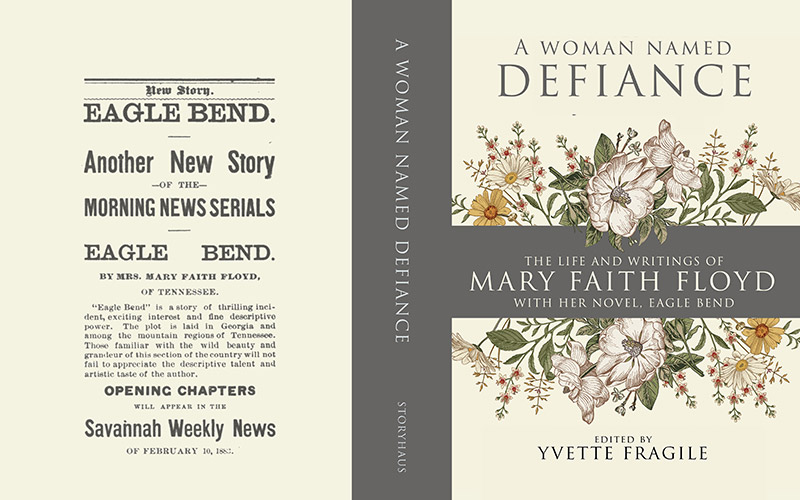

‘A Woman Named Defiance’ to be reprinted in whole

Nearly 150 years ago, a woman named Mary Faith Floyd wrote a story that spans Savannah, Ga., New York, Blount County — and the area of town in Clinton known as Eagle Bend. It was published in serial form in a newspaper, and then …

Lost.

Until now.

It’s not just any story, and she was not just any woman. Knoxville resident and owner of Storyhaus Media Doug McDaniel first learned of Floyd, who was actually a McAdoo, when he was writing a book about historic Park City. He stumbled across the McAdoo family during his research, but they weren’t relevant to what he was working on at the time.

Later, as he wrote about Historic North Knoxville, he began to write about them: Floyd, William Gibbs McAdoo, Sr., William Gibbs McAdoo, Jr., and Laura Julia Sterrette McAdoo.

McDaniel discovered that Floyd was born Mary Malinda Defiance Floyd.

She married William Gibbs McAdoo, Sr., in 1857, according to McDaniel. He was attorney general for the Knoxville circuit and a serial philanderer.

“He was a poet who wrote sonnets to half the women of Knoxville,” McDaniel said.

The McAdoos were poor. Floyd, however, was brilliant, resourceful, resilient and hard-working. She sewed for neighbors and wrote essays, literary criticism, poetry and two novels. She wrote essays about child abuse in her 1885 literary journal “The Southern Head-light,” according to McDaniel.

She was a feminist entrepreneur. She didn’t picket with the suffragettes; no, she took her own path by trying to forge her way through a man’s world.

“It was a hardscrabble life,” said McDaniel.

Bringing the story back to life took McDaniel 14 years from the time he first heard about it. Her other novel, “The Nereid,” was accessible, but “Eagle Bend” wasn’t. There was an alternate title — “Antethusia” — but he couldn’t find that either.

He would receive little clues over the years about the book. He discovered that it was printed in serial form in the Savannah Morning News, but when he and a colleague did a search at the University of Georgia library in Athens, they couldn’t find it.

Then, an epiphany. McDaniel realized the Sunday editions were not online.

He and his business partner Stephen Zimmerman spent a Sunday afternoon in Athens sifting through old microfilm until the magic moment that they found it.

If a bound edition exists, he doesn’t know of it. But it’s a story worth knowing, and so he and his team spent painstaking hours reading, recording and transcribing the words.

“It’s almost like an archeology of her words. Getting them out of the basement,” he said. “If this was never published in book form, how long did her words last? There’s an obligation to be a good steward of her words. It’s a privilege and I take it seriously.”

He wrote in the prologue to the book: “I stood still in the moment, considering the typesetters at work at the Savannah Morning News, putting her words to press. I glimpsed in my mind’s eye the men and women of Savannah, on their porches, reading her words with their tea on a sunny Sunday after church.

“I then beheld the image of archivists storing copies of these newspapers in musty basements. The technicians preparing the pages for their first preservation on microfilm.

“The librarians cataloging the reels. The decades of storage, the wonder of where these pages might be. To the moment of our rediscovery, and our own digital transformation process back to the printed page you now hold in your hand.”

Mary and William McAdoo had eight children. One son, William McAdoo, Jr., ran for president in 1920 and 1924. He became Secretary of the Treasury under President Woodrow Wilson and was instrumental in the development of the Federal Reserve. He ended up marrying Wilson’s daughter, Eleanor.

“But he wasn’t the interesting one in the family,” McDaniel said.

His sister, Laura, left Knoxville to move to Chicago and started writing book reviews. Like her mother, she married someone not worthy of her.

“Oscar Trigg was a coauthor with Frank Lloyd Wright on several works,” McDaniel said of her husband. “They were part of a literary society in the suburbs of Chicago. He was a believer in free love.

“They had a very public and lurid divorce on the front pages of the paper.”

She moved to Paris and married Pierre Gagey, a cardiologist.

“He took a mistress and Laura was once again a scorned woman,” McDaniel said. “But she reinvented herself as a salonniere. She basically scolded these men in Paris on their perception of women and blacks in the South.”

Parisian salonnieres hosted parties to promote the works of artists, philosophers and writers.

The salons were a product of the Enlightenment. Women were the hosts and decided the topics and guests, which allowed them to step into what was then a man’s world.

She died of a barbiturate overdose in the bed of novelist Anatole France.

Mary died a year later.

The story itself is about a young woman who is a struggling writer.

“She speaks very much to the nobility of the Appalachian people and their ability to learn,” McDaniel said. “She becomes a teacher in Clinton and she’s teaching her brothers. One of them ends up attending the East Tennessee University. What’s neat about this is that this is a female novelist you’ve never heard of.”

The writing style is lavish “but very readable.” The writing brings to mind novels by Anthony Trollope and even Thomas Hardy in its description of the natural world and human interactions.

The book will be released in June and can be pre-ordered on McDaniel’s website, storyhausmedia.com.