‘We trusted them’

Community pushes back on Bull Run plans

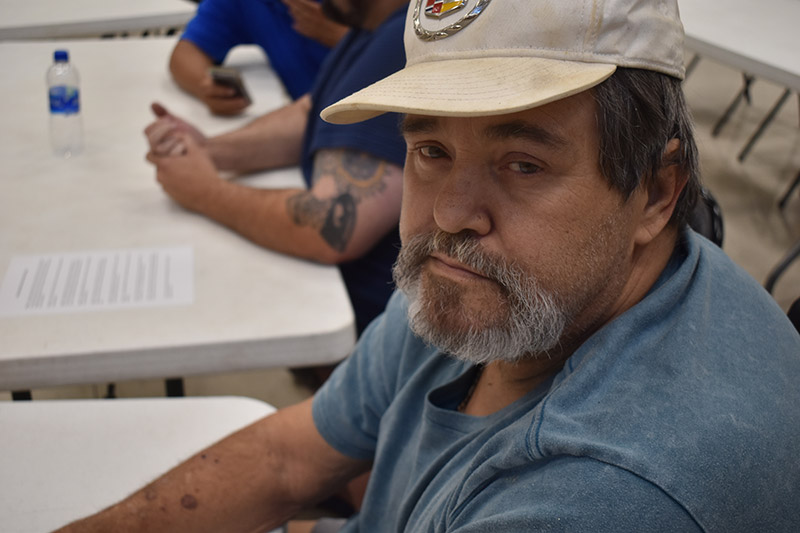

Richard Watson sold his land to TVA in 2015 with the promise that it would help the TVA stay in business for at least 25 more years. Four years later, they’re planning to shut down, and Watson regrets selling.

TVA will host two community open houses this week, with one at Claxton Elementary School on July 18 from 5-7 p.m. Last week’s meeting was scheduled to allow concerned citizens a chance to learn more from activist groups and county officials, so that they will have a better idea of what to ask during the TVA-sponsored meetings.

Bull Run is scheduled to cease operations by 2023. The big question on many people’s mind was what TVA will do with the coal ash impoundments.

Wandell represents the Claxton community as commissioner, and also has a background in the coal ash business. He did business with the TVA in the 1990s, but not with Bull Run specifically.

“I went and removed the floating ash off these ponds,” Wandell said.

There’s value in coal ash when it’s reused properly, according to Wandell. But the environmental and human health implications have been front and center lately following the coal ash spill in Kingston in 2008 and the resulting lawsuits as people have gotten sick and even died after cleaning it up. That’s what the discussion was all about during the community meeting.

Is it safe? What steps will TVA take to make sure toxins don’t leach into the groundwater? What will happen to the site once Bull Run closes? These were just some of the questions residents asked Wandell.

Wandell was joined by District 6 Commissioner Catherine Denenberg, District 3 Commissioner Josh Anderson and fellow District 1 Commissioner, Chuck Fritts.

“Hopefully we’ll get it right moving forward,” Wandell said. “[TVA] is going to work with us as community partners... and will figure out how to develop it if it’s going to be developed.”

Although Wandell has been involved with TVA and is knowledgeable about the issues surrounding the closure of the plant and coal ash, he is not an expert, and made sure his audience knew that. He did, however, answer every question he was able to.

Direct impact on people’s lives

“What I will do as a commissioner is hold TVA accountable, and when they make comments and say things to this body that I represent and this district, I’m going to make sure they do what they say,” he said. “They didn’t do what they said they were going to do in the first place. They said they were going to extend the life of the plant. That did not happen. People that sold, they sold and lost their homes based on the commitment it was going to run.”

That’s exactly what happened to former Claxton resident Richard Watson. Watson grew up on a farm on New Henderson Road, but was asked multiple times by TVA to sell them his land.

“The home we were living in, we had five acres of land and a 5,000 square foot home that my father built,” Watson said. “The home was about 25 years old and we’d just got through remodeling it. My dad passed away in that house. There are a lot of memories there. But they didn’t care nothing about no memories. They bought the farm behind me, the 75-acre farm… I was the last one on that road to sell, everyone else had done moved.”

The Watsons were asked three times to sell, and he was afraid he would turn them down one too many times and be left with an unsellable property.

So they sold in 2013.

TVA didn’t end up using the land or house, but he said he was told the Anderson County Sheriff’s Department has used it as a training facility.

“But they were in such a hurry for me to get out,” he said.

TVA told him it would be used for additional storage for coal ash.

“They told me it would be used for another 25 years,” he said. “And less than five years later they’re talking about closing it. Where do I go to get my memories back?”

When it comes to cleaning up the coal ash, he doesn’t see how that’s going to be possible.

“There’s no way they can clean all that up,” he said. “They dumped it in the lake back there. They made a road as a barrier, then filled it all in. And when they got that all filled in, they started dumping it in the front. And they told me the one in the front was almost full and they could get maybe two more years out of it. And then they’d have to start dumping it somewhere else.

“We trusted them. We could have stayed where we were at.”

Watson’s family was displaced from Oak Ridge back in the 1940s when the national labs were being built. It was the Scarboro branch of his family, according to Watson. That’s when they were given the Claxton land, but even that was partially taken from them when a road was built that cut through their property, according to Watson.

“Just one thing after another,” he said.

TVA spokesperson Scott Brooks told The Courier News that the current plans for the ash are temporary.

“This is not a final decision to store coal ash permanently at the main ash impoundment nor anywhere else at Bull Run,” Brooks said. “We haven’t made any decisions about the future of coal ash at Bull Run.”

The plan is to close the main ash impoundment in place and turn a section of the impoundment into a temporary process water basin, according to Brooks. That plan will be in place until a permanent decision is made on what to do with the ash. The current “stilling pond” would be permanently closed, according to Brooks, with ash removed to an existing onsite landfill and turned into the permanent process water basin.

Editor's note: this story has been updated to reflect the year the Watsons sold the land to 2013. It originally said 2015. It has also updated Watson's story to include what branch of his family sold their Oak Ridge land.