After 14 years, there are still surprises for the Lenoir Museum’s curator

Ranger Michael Mlekodaj, curator of the Lenoir Museum, has worked for Norris Dam State Park for 14 years now.

“I started in 2007,” said Mlekodaj. “Before I found the job, I taught history and geography. I had been here during a field trip, and I knew the place and the park and I thought it would be great. I’ve been here ever since.”

Mlekodaj said that the job has changed in myriad ways since he started.

“The biggest is technology,” he said. “Everyone is much more tech-savvy since I started. You know, people were using flip phones when I started, and in some ways that technology has made things easier. With social media and stuff, we can get our programs out there a lot easier. Overall, it’s helped us promote in a big way. We can take videos and stills of events as they’re happening, so I think it really has helped us a lot. Our online presence has helped too, with our web-page and Facebook and Instagram.”

To Mlekodaj, though, the museum is even more important now that the world is so connected, and now that people are so tech-savvy.

“This is a kind of break from that high-tech world. You can come here and see how life was before all of that. We’re using so much more technology and everyone is looking at their screens, but it’s our job when they come in to get them to put the phones away and focus on these artifacts so they can think about life before that technology.”

Mlekodaj said that even after 14 years, one thing that still surprises him is the wide range of people who come through the park and see the museum.

“You think ‘OK, we’re in Anderson County,’ but we’re not far from I-75, so we’ve got Michiganders and Ohio people and people from all over the country and the world that have come here. I’ve had people from Vietnam and sub-Saharan Africa and quite a few Australians come through. It’s interesting to see. It’s surprising in a lot of ways.”

When asked if there’s one thing in the museum that everyone, no matter where they’re from, tends to gravitate toward or immediately make a beeline for, Mlekodaj said both yes and no.

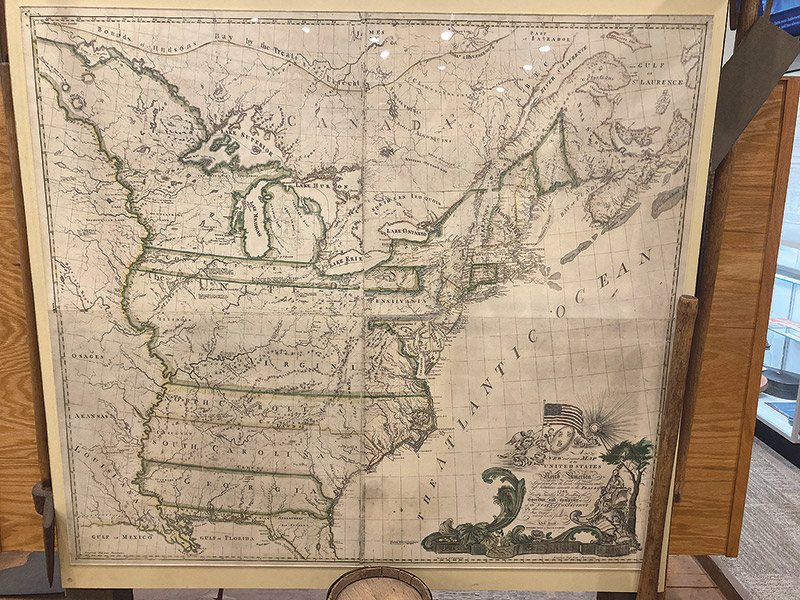

“Honestly, almost from the front door, I see families kind of scatter. There’s a little bit of everything in here and people always gravitate towards what they’re interested in, but a lot of people always gravitate towards our old map. It’s called the Buell Map and it was the first one following independence and people love coming in and trying to find their town on it. Then apart from that, the barrel organ is another.”

Mlekodaj said the barrel organ, alongside the large burial urn, are some of his personal favorites of the museum.

“My absolute favorite piece in the museum is the burial urn from the year 500 AD. It was found in a cave in North Georgia. There were bones in there when it was originally found, and that’s my favorite piece because I can remember seeing it when I was a child and they still had the bones in there like when it was found. There’s a federal law now where you can’t have Native American bones on display, but that wasn’t the case back in ’84 when I was a kid.

“The crown jewel of the museum, though, would be the barrel organ. It’s 1820s and works via a crank. All the different levels move and all the characters have little actions they do.

“It wasn’t working when we originally got it, and two guys in Norris spent somewhere around 500 man hours putting it all back together.

“One of them was a machinist and actually had to create all-new parts for it because we were missing some.”

Mlekodaj finished by talking about his hopes for the museum and it’s relationship with the community going forward.

“A lot of people stumble on us,” he said. “I don’t think the public knows everything we offer. The park has been here forever, but I wonder if they really understand how much we offer.

“There’s so much here, and I just hope that more people see that.”