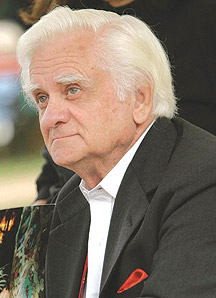

John Rice Irwin passes at age 91

JOHN RICE IRWIN

His family was blessed to be by his side when he drew his final breath, they said.

A graveside service will be held at Norris Memorial Gardens at 3:30 p.m. on Thursday, Jan. 20. The procession will leave from Holley-Gamble Funeral Home in Clinton at 3 p.m.

A celebration of the life of John Rice Irwin will be held at the Museum of Appalachia at 2 p.m. Sunday, April 24.

“How incredibly blessed we have been to have a man in our midst who was so deliberate about bringing people together to share music and stories, and preserve the history of our Appalachia,” Anderson County Mayor Terry Frank said of Irwin.

“He understood the value of knowing where we’ve been, of who we are, and the incredible community bonds that kind of understanding and appreciation creates in us as a people. He will be greatly missed, but he has left an incredible legacy that will never be forgotten -- a legacy his family and our community will continue to build upon.”

Irwin was born on Dec. 11, 1930, in Union County, Tennessee.

While he was still a toddler, his family was forced to move from their farm to make way for the flooding of Norris Lake and the construction of Norris Dam. They first settled in Robertsville, but the Manhattan Project forced them to move yet again, this time to the Bethel community.

For as long as he could remember, Irwin was captivated by the rich cultural history of East Tennessee and its people. As a young boy, he would sit at the feet of his grandmother, Ibbie Jane Rice, and grandfather, Marcellus Moss “Sill” Rice, and listen intently to their stories of the past.

Sill took notice of his grandson’s fascination and said to him, “You ought to keep the old-timey things that belonged to our people and start you a little museum sometime.”

It was this advice that would ultimately inspire Irwin to create the Museum of Appalachia.

After graduating from high school, Irwin served in the United States Army, and was stationed in Germany during the Korean War.

After his discharge, he returned to East Tennessee and used the G.I. Bill to continue his education, earning a bachelor’s degree in history from Lincoln Memorial University and later a master’s degree in international law from the University of Tennessee.

It was while attending Lincoln Memorial that he met and later married Elizabeth McDaniel Irwin, a union that produced two daughters, first Karen, and then Elaine. John Rice and Elizabeth were married for 53 years until her death in 2008.

Irwin taught for several years in public schools and colleges.

In 1962, he became the youngest superintendent of schools in the state when he was elected to the position in Anderson County at age 31.

Irwin spent his free time traveling throughout the hills and hollows of Southern Appalachia collecting “old-timey things,” and more importantly, the stories behind them.

He bought a historic cabin and placed it on his family property in Norris. With extreme attention to detail, he tried to recreate what the cabin would have looked like when it was built in 1898.

Before long, the Irwin family welcomed friends and visitors to view their unique collection. It became so popular that it interrupted the Irwin family’s daily life, so the family began charging a nominal fee.

The museum officially opened in 1969, and hosted about 600 visitors that year. Today, the museum regularly sees tens of thousands of guests per year.

In 1980, Irwin retired from teaching and devoted all his time and effort to developing the museum. With the help of Irwin’s family, the museum would eventually grow to house 35 log structures, including the cabin of the Mark Twain family, plus three large exhibit buildings that house tens of thousands of Appalachian artifacts.

Irwin also hosted special events at the museum, including the Tennessee Fall Homecoming — a music and heritage festival that had a nearly 40-year run.

It was during the 1980s that the museum exploded in popularity, largely due to the promotion and praise of notable Tennesseans such as then-Gov. Lamar Alexander and writer Alex Haley.

After visiting the museum, Haley purchased a farm across the street and spent the rest of his life singing the museum’s praises.

In 1989, Irwin won a MacArthur Foundation fellowship, which he used to build the museum’s Hall of Fame. He received a variety of awards throughout his career, including honorary doctorates from Lincoln Memorial University, Carson Newman University, and Tusculum University.

Irwin published numerous books on tenets of Appalachian life, including baskets, guns, quilts, and music. A 20-year friendship with a remarkable Tennessee mountain character led to the publishing of his most popular work, “Alex Stewart: Portrait of a Pioneer.”

Irwin operated the museum until it was converted to a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization in 2003. He served in an advisory role for the next decade, during which the museum achieved

recognition as a Smithsonian affiliate.

When asked about his friend’s passing, Lamar Alexander said, “John Rice Irwin displayed Appalachian pioneer history in a way that no one else ever has. His tens of thousands of items in the Museum of Appalachia remind us that we don’t have to go outside our own backyards to find interesting people.

“For 60 years, he stayed up late into the night writing books and matching artifacts with stories so that we could better understand who we are,” Alexander said. “He taught us about ancestors who made or grew things instead of buying them. He was an engaging genius and a generous friend. Honey and I will miss him greatly.”

Irwin was preceded in death by his father, Glenn G. Irwin; mother, Ruth Rice Irwin; wife, Elizabeth Ann McDaniel Irwin; daughter, Karen Ann Irwin Erickson; and nephew Robert David Irwin.

Survivors include his daughter, Elaine Irwin Meyer and her husband, Edward William Meyer III; his brother David and wife, Carolyn; and his three grandchildren, Maia Lindsey Gallaher and husband, Jason Gallaher; John Rice Irwin Meyer and wife, Sara Meyer; and Edward William Meyer IV.

He was also blessed with five great-grandchildren: Rese, Avery, Meyer, Landry, and Parker. He is also survived by a plethora of relatives, including niece Anne Irwin Buhl and grandniece Katherine Buhl.

Irwin dedicated his life to preserving the rich heritage of the people of Southern Appalachia, and nothing would please him more than for that preservation to continue for generations to come, the museum said.

Donations made in memory of John Rice Irwin may be made to the Museum of Appalachia, P.O. Box 1189, Norris, TN 37828.