The ‘poor farm’

Historical marker now labels site in Claxton

For decades in the 19th and 20th centuries, poor people with disabilities such as blindness, deafness and mental health issues lived as “inmates” at Anderson County’s Poor Farm.

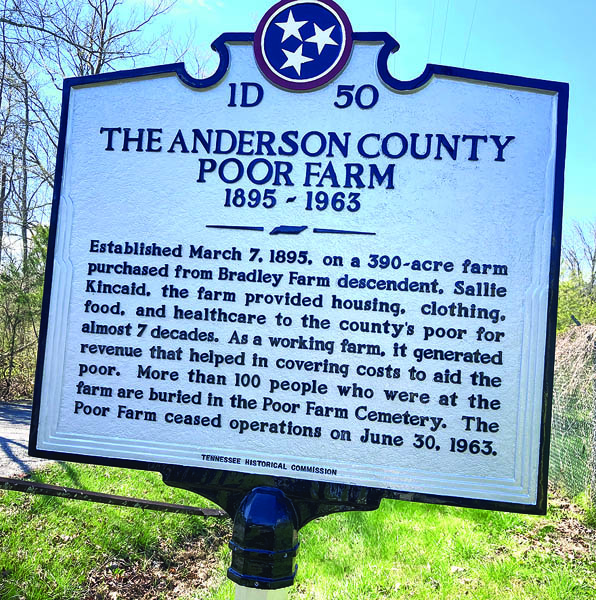

The Poor Farm site in Claxton got a Tennessee Historical Commission sign thanks to the efforts of Anderson County historical researcher Leo York. York unwrapped the marker at an event at 1 p.m. Saturday, March 18. The marker is on Nature Lane near the intersection of Old Emory Road and Blockhouse Road. More than 20 people attended the event including Anderson County Commissioners Catherine Denenberg and Anthony Allen.

“I don’t want this history to go away,” York said at the event. “It needs to be talked about now. That’s why we’re putting this up.”

The sign explains some details of the site’s history.

The county established this poor farm on March 7, 1895, although it was not the first one for the county and opened after the first one closed. The Poor Farm provided clothing, food and health care, the sign stated, to the county’s poor. York said the farm’s revenue as a working farm covered these costs, sparing county taxpayers. York explained at the event that the poor people were sent there by the county government.

“They were referred to as inmates; not residents or anything nice that we would use today,” he said. “They were actually required to stay here because most of them were ordered here by the court, the Quarterly Court, which nowadays we call the County Commission, and they were ordered here by the county judge, who nowadays we call that the county mayor.”

More than 100 people who lived at the farm lie in its cemetery, as per York and sign. The institution ended operations in 1968. York said at the event that the site’s inmate population peaked in 1935, although he said it was difficult to get precise numbers.

“Learn the history and learn not to repeat it,” York said regarding what people could take from learning about the Poor Farm. “It wasn’t the best system, but for the time, it was the best system. It was the only system that we had.” He said all counties and all states had similar systems.

He said these poor farms were “more a benevolent, caring sort of thing” than the Victorian workhouses with their forced labor.

York said he sent the information to the Tennessee State Historical Commission to get the marker put in place.

“If we didn’t do something like Leo has done, the history would soon be lost completely,” D. Ray Smith, an Oak Ridge resident and board member of the Tennessee Historical Commission told The Courier-News. “The buildings are gone. Even the graveyard only has one headstone.”

York explained the Poor Farm’s residents included John Hendrix, a man believed to be mentally ill but later described in legends as having predicted World War II and the founding of Oak Ridge by the federal government. He later escaped. York recounted a legend stating Hendrix said it was an evil place, that lightning would strike the facility and it would burn, which he said it did.

“When the farm first opened, the buildings actually did have iron cages in them,” York told the crowd. In its earliest days the Poor Farm had six cottages, each with two rooms. “They tried their best to keep the women and the men separated,” York said. “That didn’t always work because there were several births.” Also, the site had tall fences around the cottages. He said many residents probably had Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. He said the inmates weren’t required to work because many weren’t able, and that tenants, not inmates, did much of the farm work.

The farm was 390 acres total, York said, adding that the land it formerly occupied stretched all the way to the area across from Calhoun’s in Oak Ridge.

He said the farm ended due to the government feeling like it was “no longer needed” after welfare programs began. The farm’s buildings, he said, are all gone.

He said people considered it “degrading” and even nowadays some people don’t want to admit they had relatives who lived at the Poor Farm.

York said a book he wrote based on his Poor Farm research is in the Oak Ridge and Clinton public libraries.