Life during wartime Oak Ridge depicted at history museum

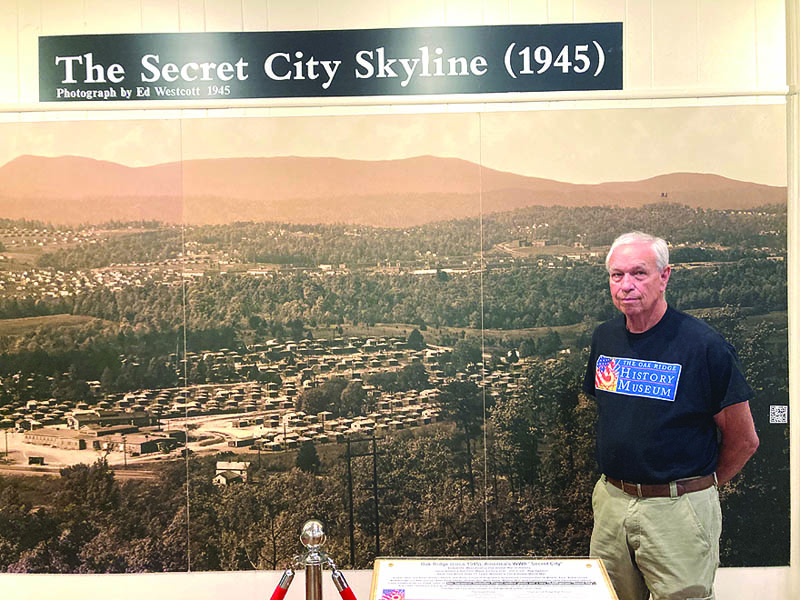

Don Hunnicutt, tour guide coordinator at the Oak Ridge History Museum, poses next to a view from above of early Oak Ridge in 1945. (photo:Ben Pounds )

Visitors to the Oak Ridge History Museum can learn what life was like in Oak Ridge during the war and the years afterward.

The federal government founded Oak Ridge as a city behind a fence in 1942.

The town held the people working on uranium for “the gadget,” later revealed as the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The museum is in a historic building, the Midtown Community Center, later Wildcat Den, at 102 Robertsville Road, built in February 1945.

“Most all the people that visit this museum are in awe of how all this happened in three-and-a-half years, and how it was such a secret,” Don Hunnicutt, tour coordinator for the museum, said of the town’s wartime operations and construction.

A display states the government funneled early shipments through surrounding towns.

But “even the Tennessee mountaineers could see that Elza, Tennessee, with a population hovering at a top figure of 151, couldn’t use 15,000 toilet fixtures,” the display notes.

“We weren’t on a map; no one knew what was going on,” Hunnicutt said.

Fences surrounded the city during the war, and people needed badges to enter if they were 12 or older.

He said the people in town usually made more than what they made in their old communities, and the average age was 27. There were two women to every man.

“If you want to go back in time, this is the museum you come to to see how things were back in the ’40s here in Oak Ridge,” he said.

Large panoramic photos show the town’s different areas as they appeared in 1945.

A reconstructed “hutment” shows the spare one-room life of many African Americans and some white construction workers in those early days.

Other rooms show the furnishings of other types of residences like dormitories and flattops, along with youth life, security, sports and the early Oak Ridge Fire Department.

Photos show people gardening and at shops and cafeterias. Other small exhibits and artifacts come from the time before the war and from the communities that pre-date Oak Ridge.

Hunnicutt gave some details of the building’s history.

“As the name implies it was a community center for people to come in and have social activities as well as the Red Cross used it for training purposes,” he said. After the war the city inherited the building, making it the Wildcat Den, a place for the city’s high school students with a juke box, ping pong and sometimes dances with bands.

In later years it served as Oak Ridge’s senior center before that institution moved.

Planning for the museum dates to 2018 when the American Museum of Science and Energy, run by the Department of Energy, moved to a smaller location and shed several exhibits on history in favor of a scientific research focus. The Oak Ridge History Museum acquired some of AMSE’s former history displays.

“This museum tells the story of what happened here in the Manhattan Project. The Museum of Science and Energy tells the story of what Y-12 and ORNL’s doing,” he said. “That’s the reason we opened this museum. To tell the story or it wouldn’t have been told.”

“This Manhattan project was a phenomenal project that happened back then. It will never happen again for the simple fact that secrecy was the number one thing besides the design and operation of the nuclear plants. You can’t get that today. Cell phones prohibit the secrecy.

A special gallery focuses on photographs from the late Ed Westcott, a US Army corps of Engineers photographer and Hunnicutt’s father-in-law.

He was the only person authorized to photograph Oak Ridge during the war. The exhibit includes some pictures that have never been published before and the largest group of photographs by Westcott in the world.

“Without his photography, we wouldn’t have anything to show what transpired here in Oak Ridge other than everybody talking about it,” Hunnicutt said.

“His photographic work was quite unique in my opinion, and I’m not being biased about it, other people have commented on it as well,” he said.

“His capturing of different situations: people, people’s activities, kids’ activities, everything basically that’s happened in the city along the way, he’s got a photograph made about it.”

Westcott also took pictures of the wartime nuclear plants’ construction and operation.

Admission is $8 for students, veterans, current military and first responders.

Other adults pay $10, and children under 12 enter free. The group rate is $8 per person. The museum is currently open Thursdays and Fridays from 10 a.m. until 2 p.m. and Saturdays from 10 a.m. until 3 p.m.