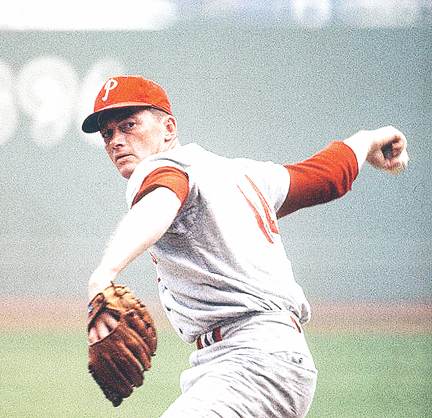

Remembering a Hall of Famer and friend

When Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Jim Bunning threw a perfect game against the New York Mets at Shea Stadium June 21, 1964, — Father’s Day — future Clinton businessman George Krebs could take pride in the fact he and his boyhood friend had started playing baseball together almost 30 years prior to that day.

Bunning — whose perfect game was the first in the Major Leagues since 1922 and the first in the National League since 1880 — learned to pitch as an elementary school student on a field in Southgate, Ky., with Krebs catching those pitches.

“We were friends from the time we started school and stayed in touch through the years,” Krebs remembered of his friend who died last year at age 86. “Our wives were friends from the beginning when they were our girlfriends as kids. Jim taught me to drive in his father’s 1937 Chevrolet (without Mr. Bunning’s permission) and I was honored to sit in the front row when Jim was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame (1996) and was further honored when he recognized me during his acceptance speech we were playing baseball together from the beginning.

“He still has a swollen hand from the unmatted catcher’s mitt he used back then,” Bunning said of Krebs during his Hall of Fame induction speech in 1996.

Southgate is located five miles south of Cincinnati — an area which has always been a hotbed for youth baseball. Although Bunning and Krebs played for separate high school teams, they played together on other summer teams where Krebs caught Bunning’s pitches.

“Jim was a good baseball player at all positions — a good overall athlete — but all he really wanted to be when we were kids was a pitcher,” Krebs said of the future of Famer and later U.S. congressman and U.S. Senator.

Krebs said early years of their baseball experience found the older kids usually pitching, but Bunning was always figuring out ways to work to improve his pitching skills.

“If we were not playing a game on a given night, Jim and I would play catch in the back yard after dinner until it got dark and that is when he developed into a good pitcher,” said Krebs, who owned the Chevrolet dealership in Clinton over almost 25 years. “The older Jim got, the better a pitcher he became.”

Bunning went to Cincinnati’s Xavier University on a basketball scholarship. He signed with the Tigers in 1950 and played five years of Minor League ball before he was finally called up to Detroit in July 1955. Krebs said Bunning was seriously considering quitting baseball when he finally got the call to Detroit.

“He and (wife) Mary visited us on their way to spring training in 1955 and was ready to give it up because he had played all these years in the minors with mixed results and his father-in-law thought he should give up baseball and get a real job,” Krebs said. “He did start in the minors that year, but he was pitching better and he finally made it that summer.

Bunning’s Major League record was 224-184 with a 3.27 ERA as his career spanned 591 games — 519 starts with 151 complete games over 3,760 innings — spread between the Tigers, Phillies, Pittsburgh Pirates and Los Angeles Dodgers from 1955 through 1971. He won 20 games in 1957 and was a 19-game winner four times. His 2,855 strikeouts rank 17th in the Major Leagues. He is one of only five pitchers to throw no-hitters in both the American and National leagues.

The June 21, 1964 perfect game against the Mets was the first such performance in the Major Leagues since 1922 and the National League since 1880. His American League no-hitter for the Tigers occurred over the Orioles July 20, 1958 in Detroit.

After his playing career, Bunning managed in the minors before entering politics. He served in the Kentucky Legislature, was an unsuccessful candidate for governor of the Bluegrass State and later served in the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate before retiring in 2011.

The Bunnings had nine children, 39 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren. His son, David, is a federal judge. Grandson Patrick Towles played quarterback for the Kentucky Wildcats in 2012, ’14 and ’15.

Bunning was frustrated he kept missing election to the Hall of Fame, but Krebs encouraged him to not give up hope.

“Jim didn’t agree with me, but I kept telling him he was going to finally make it to Cooperstown and I was going to be there to watch him get inducted,” Krebs said. “He didn’t think it would ever happen, but it did and I was so proud of Jim when my longtime friend became a Hall of Famer.”