Settlers along the Wilderness Road, Part 3

Life was tense in the 1770s From the Mountains

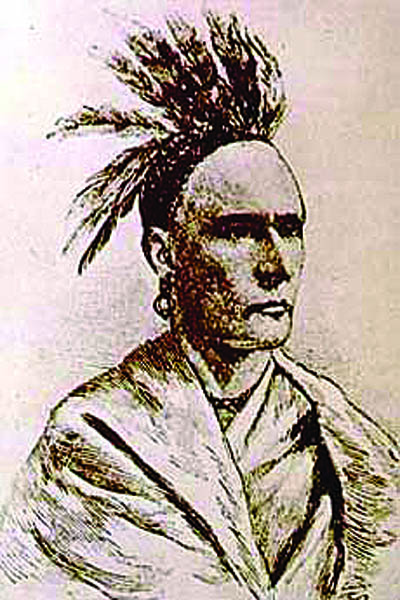

Chief Logan (Ohio History Central)

He developed an intense hatred of the Indians and attacked all that he encountered. He was persuaded to join the border guard in order to avert further troubles.

Daniel Boone, Rebecca and the family settled down for the winter in a cabin in the Sinking Creek area between Dungannon and Castle’s Woods. It belonged to Captain Gass. Daniel supported his family by hunting. His son, Israel, accompanied him on almost every trip.

“You’re nearly a grown man now, Israel,” Daniel told his son one day. “I need you to watch over your mother and the rest for me while I go to Kentucky.”

“When are you taking us to Kentucky?” Israel asked his father.

“Israel, it’s more dangerous for settling now than it was before. Captain Russell has heard of settlers swarming down the Ohio River, and the Indians are fighting war on every path.

“They are unhappy about losing their hunting grounds.

“That Crabtree man who was with James when he was killed has murdered a Cherokee down on the Watauga. The Cherokee Nation is threatening to join all the northern tribes and go to war against us. It’s not a good time to take you all until everything settles down.

“But I must go for these very reasons. Some people have received land grants in Kentucky, and John Floyd and his men are surveying it.

“Governor Dunsmore wrote Captain Russell that war is breaking out and that someone has to tell Floyd and his men about the impending attacks. Captain Russell believes that Michael Stoner and I can find them and warn them of their danger.

“I need for you to help me, Israel. Watch out for all of the family for me. If the Indians start striking too close, you must see that your mother and the children get over to Moore’s Fort.”

On June 27, 1774, Israel and the remainder of the family bid Daniel and Stoner goodbye as they set off down the Pellissippi River, which is the Indian name for the Clinch River.

“Will we ever see them again?” Israel’s sister Jemima asked with tears in her eyes.

They were already worried so much about Indians that they could hardly sleep.

When they did fall asleep, Jemima and the others would often be startled awake by the barking of the dogs or by the screaming of a distant panther or other wild animal.

Cries of joy welcomed Daniel and Stoner when they returned Aug. 27.

All of the Boones gathered around as they hugged and kissed the tired Daniel following his perilous 800-mile trip on foot.

“I put in a claim for land when I found them,” Boone told his family as he rubbed his aching feet. “And I took time to build a little log house for us to stay in while we get started. We’ve got land and a home in Kentucky. Someday we’ll go there.”

“Goody, goody,” Jemima and her sister Lavina intoned as they danced around the cabin.

Most of the men were gone when Daniel Boone and Michael Stoner returned from warning surveyors in Kentucky of the Indian uprising. It was 1774 and the men had departed for the Ohio River to help quell an Indian uprising.

Within a few days, Daniel organized a small troop of men and proceeded northward to fight Chief Cornstalk and his warriors. Boone’s group was soon overtaken by a messenger with orders to return.

They were needed to defend the area’s fortifications, particularly Moore’s Fort.

Efforts had been made to strengthen Moore’s Fort when word came that Logan, chief of the Mingoes, had ravaged Fort Blackmore and killed two men and a number of cattle.

Daniel Boone, Israel, and several of the men went 20 miles down the river to help them.

Captain Blackmore showed Daniel a Cherokee war club that was left behind during the ambush.

The war club indicated to Daniel that the Cherokees had joined the warring Indian nations to the north.

“Men, this means war right here on the Clinch,” Blackmore said. “Martin’s, Mump’s, Moore’s, all of the forts are in danger. We have only 11 men here. We need more. We need a captain over all of our forts. Boone, will you take our command?”

Boone sat silently before saying, “If you need help, call on us. We’ll come. You must always stay alert. Put out sentries and keep a close watch in every direction.”

They returned to Moore’s Fort and found everyone within the stockade hungry and frightened.

The women and children were afraid to go outside and milk the cows, and the men had abandoned their hunting in the woods in fear of Logan’s warriors. They only made short trips outside to set and check animal traps.

Logan was a mighty hunter, excellent marksman, and a “friend of the white man for many moons.” He was liked and respected for his honesty and loyalty by the whites and Indians alike. He was kind to women and children and treated everyone with dignity.

Logan expected his courtesy to be returned, but several of his relatives had been killed by settlers years before.

He put that behind him, but on April 30, 1774, a company of nine Indians including several of his family left his camp to visit a man by the name of Greathouse.

Greathouse proceeded to get the Indians drunk and then he and his associates cruelly murdered them. Chief Logan was crushed. It was more than he could stand.

He began at once to raid settlements with small bands of Indians. On the first series of raids, he took 13 scalps, six of them being children.

In July 1774. the Mingoes captured William Robertson and condemned him to be tortured at the stake.

Logan offered his freedom in exchange for assisting him in writing a letter to Captain Cresap, whom he blamed for the death of his family members. Robertson gladly complied in order to save his skin, although he had to rewrite the letter three times. Each time, the angry chief wanted the message to be more stern.

Logan then visited the Cherokees and induced some of the bloodthirsty young warriors to join him.

A few days later, a messenger arrived at Fort Blackmore telling of Logan’s warriors attacking the Holston settlement.

“They struck John Roberts’ home and killed all but one,” the message read. “All of the dead were scalped.”

“To Captain Cresap,” began a letter Logan left behind.

“Why did you kill my people on Yellow Creek? The white people killed my kin a great while ago and I forgot about it. But you killed my kin again on Yellow Creek and took my cousin prisoner. I then decided I must kill, too.” Logan’s mark concluded the statement.

Boone spent more time on watch and changed the sentries frequently in an effort to keep them alert. The women and children stayed inside the fort except for short trips to fetch water.

The trips taken by the men were short as well, mostly to set traps and to check them periodically.

“Logan and his men are in the woods,” one of the trappers yelled as he hurried back into the fort one day. “He shot John Duncan. We have to hurry if we are to save him.”

When Daniel and the men arrived at the scene, they found Duncan dead. He had been scalped. Boone and the men pursued the Indians cautiously and diligently deep into the night, but they were not to be found.

Copyright 2022, Jadon Gibson

“I’m a warrior, not a peacemaker,” Chief Logan says as he refuses to sign a peace treaty in Jadon’s “From the Mountains” next week.

Jadon Gibson is a freelance writer from Harrogate. His stories are both historic and nostalgic in nature.

Thanks to Lincoln Memorial University, Alice Lloyd College and the Museum of Appalachia for their assistance.