Beware of Micajah and Wiley Harpes, Part 4

From the Mountains

They camped at night, replenishing their strength before resuming their quest each morning. When regulators were close on their tail, they slept both day and night.

“Their victims lay face up in rivers, gutted and their eyes wide and staring, their innards replaced with stones,” Jim Ridley wrote.

“Or they lay hacked and strewn in the Cumberland wilderness left to any animal’s appetite. They were killed for the gold they carried and did so despite the kindness they gave. The killers drew no distinction between men and women, boys and girls, children and infants, not even their own.

Moses Stegall joined a posse seeking the Harpes the morning after his wife and child were viciously murdered. They were bent on finding the Harpes and making them pay for their misdeeds.

The posse found two additional victims of the Harpes as they rode, swelling the number of deaths at their hands to 30. It could have been more or less.

Eventually they came upon the Harpes’ camp, abandoned except for Wiley Harpes’ wife Sally who explained the others had recently left.

They rapidly followed their trail and came upon them after two miles.

They called for Big Harpe to throw down his weapons and dismount but he quickly spurred his horse into a gallop in order to escape.

The Harpes never obliged attempts at arresting them. Members of the posse shot at the fleeting forms with most of the bullets whizzing by until one hit Big Harpe in the leg. It didn’t seem to slow the fugitive as he rode on continuing his quest to escape.

When one’s life is at great peril pain is of little consequence.

John Leiper missed on his shot but grabbed a loaded gun from posse member Tompkins and spurred his horse ahead after Harpe.

Micajah didn’t see the weapon exchange and knew Leiper couldn’t have taken time to reload. He slowed and began turning his horse to get a good shot. Leiper had closed the distance between the two and was able to fire as Harpe was turning his horse. The bullet struck him in the spine.

Big Harpe’s body contorted uncontrollably causing his reins and rifle to fall from his grasp. He was losing a lot of blood as the posse caught up with him barely hanging from his mount. They gave no attention to his predicament as they pulled him off his horse.

“Water,” Harpe was barely heard pleading for a drink under his breath but it was still loud enough to be heard.

Leiper pulled off one of his shoes, filled it with water and held it to Harpe’s mouth to drink. Paralysis had already settled in and Big Harpe’s hands were uncontrollable.

“Harpe, why did you kill that woman and her baby,” Leiper asked him.

“They wouldn’t let a man sleep and I put ‘em outta their misery,” he replied sarcastically. “They’re burned up in the fire but ye needn’t worry none. They’ll be able to find another wife.”

Leiper was infuriated. He searched for a weapon before grabbing Harpes’ own butcher knife and proceeded to start cutting off his head. Micajah Harpe was mortally wounded and was resigned to dying.

“You’re doin’ a mighty sorry job of that,” Harpe gargled toward Leiper causing him to become more efficient as he completed his task.

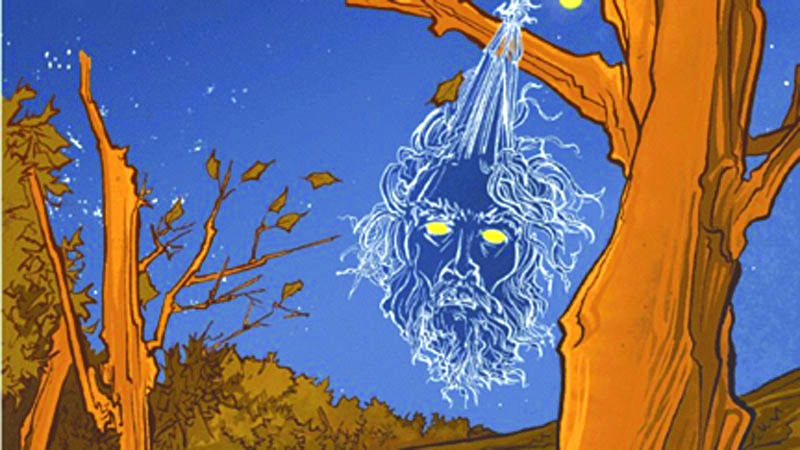

Harpe’s head was put in a saddlebag and later wedged in a crook in a tree where the road from Henderson forks with one going to Marion and Eddyville and the other to Madisonville and Russellville. The area became known as and is still referred to at times as Harpe’s Head.

Copyright Jadon Gibson 2023. Jadon Gibson is a widely read Appalachian writer from Harrogate. His writings are both nostalgic and historic in nature. Thanks to Lincoln Memorial University, Alice Lloyd College and the Museum of Appalachia for their assistance.