The rise of Memphis as center of cotton and slave trade

A few years after the War of 1812, the U.S. government acquired present-day West Tennessee from the Chickasaw Nation.

Andrew Jackson represented the U.S. government in this 1818 transaction, which most textbooks refer to as the Chickasaw Purchase. After it occurred, the Chickasaw Indians were forced to move to present-day Mississippi.

Settlers quickly moved into West Tennessee, creating one of America’s first land rushes.

People organized counties and towns with speed — a process well-documented in newspapers of the time.

Named for a city in ancient Egypt, Memphis was one of about 30 of these towns.

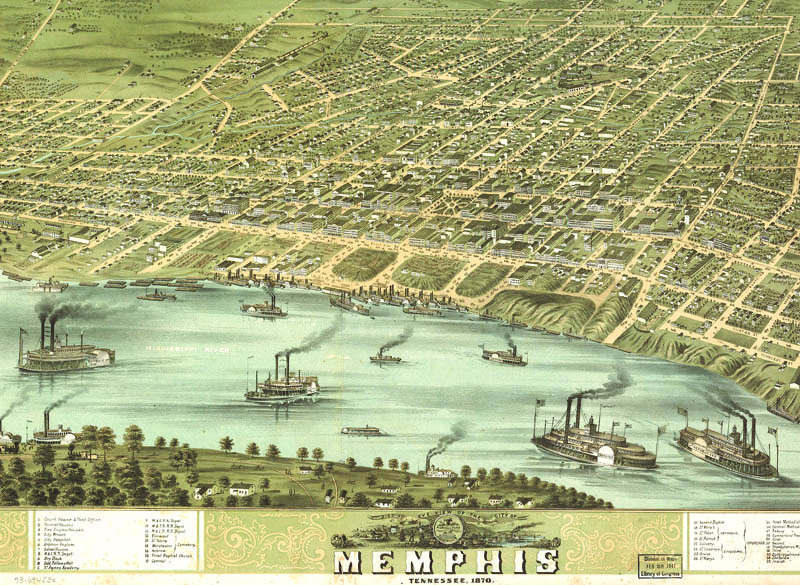

It eventually emerged as the largest, because it was on the Mississippi River, its riverfront was stable, and its founders were John Overton, James Winchester and Andrew Jackson.

“[The] town of Memphis has been laid off by the proprietors on the Chickasaw Bluff, on the east bank of the Mississippi, 224 miles below the mouth of the Ohio,” reported the July 3, 1820, Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette.

“The site of this town is believed to be the handsomest on the Mississippi below St. Louis.”

As settlers moved into West Tennessee, they harvested its natural resources. At first, this meant cutting down trees, dragging them to the nearest river, and floating them downstream to a place where they could be sold for lumber.

By the 1830s, Memphis had become the center of the Mid-South’s hardwood industry. The city sent hardwood downriver to New Orleans, and upriver (via steamboat) to St. Louis and points further north.

After West Tennessee’s thick forests were cleared, farmers began planting crops.

It didn’t take long for it to become obvious that cotton grew wonderfully in West Tennessee, and large cotton plantations were established.

These plantations needed labor, and that largely meant enslaved labor. In the 1820s and 1830s, enslaved people from places such as Virginia, Maryland and East Tennessee were sold and forced to move to West Tennessee. By the 1850s, West Tennessee had more slaves than the other two grand divisions of the state.

Located on the river, and at the junction of three pro-slavery states, Memphis soon became the center of the region’s slave trade.

Bolton, Dickens and Company was Memphis’ first big slave-trading firm, and one of the largest slave-trading businesses in American history.

The company had buying offices and “slave marts“ — as private slave prisons were known — in Memphis, New Orleans, Vicksburg, Mobile, Lexington, Richmond, St. Louis and Charleston.

To summarize the general business plan, Bolton, Dickins and Co. sent agents to places where enslaved people were no longer needed, bought them, and forced them to move to markets where they could be sold for more money. By 1846, ads for Bolton, Dickens & Co. were a regular feature in newspapers such as the Tri-Weekly Memphis Enquirer. “We are now in receipt of 25 Negroes, consisting of men, women, boys and girls, as likely as was ever offered in this market,” one ad proclaimed.

Bolton, Dickens & Co. might buy 20 slaves from someone in St. Louis and sell them to someone in New Orleans; or buy 50 in Memphis and sell them in Vicksburg, Mississippi; or buy 100 in Vicksburg and deliver them to Texas.

However, in May 23, 1857, Bolton, Dickens & Co. President Isaac Bolton shot and killed another slave trader named James McMillan at the firm’s Adams Street headquarters. McMillan died a few hours later, and Bolton was tried for the murder.

At least seven lawyers were hired to defend Isaac Bolton, and he was somehow found not guilty.

However, the crime and the publicity that surrounded it resulted in the decline of Bolton, Dickens & Co.’s business and the rise of business of a competing slave trader — the man to whose office McMillan had been carried after he had been shot.

That completing slave trader was Nathan Bedford Forrest. By 1858, his was the largest slave-trading firm in Memphis.

Speaking of Nathan Bedford Forrest, since his name is also slated to be removed from Tennessee’s eighth-grade social studies standards, a column next month will be about him.