Journals of another era, another lifestyle

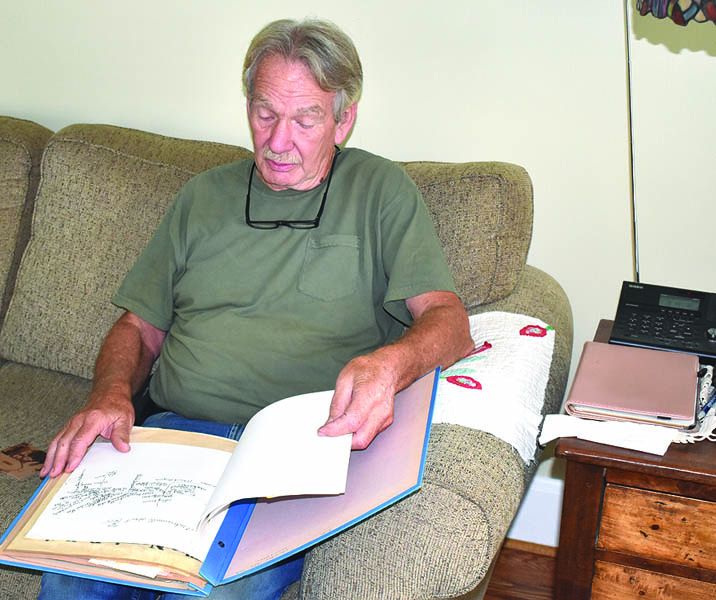

Don Sharp looks at a hand-drawn map of Andersonville as it appeared 1912-15 in the journal written by his father. He is sitting in the living room of the house in Ander- sonville where he was born. The house was built around 1890. (photo:Pete Gwada )

The journals were written in 1989 and contain fascinating descriptions of life in Andersonville in the early 1900s. His father, Claude E. Sharp, was born in 1906, and his mother, Helen Wallace Sharp, was born in 1913.

Life was very different at the beginning of the last century. Most people had cattle, chickens, and vegetable gardens, maybe even ducks and turkeys.

Sharp’s mother said there was work to be done on the farm, but also time for play with her eight brothers and sisters.

Of course, there were no electronic screens to stare at. They played such games as hide and seek, kick the can, and checkers. She picked blackberries in the summer. After they had picked all the berries needed for canning, the remainder was sold for 25-cents a gallon.

One of Sharp’s father’s early memories was of his mother, Sharp’s grandmother, giving each one of the children an egg. They would take the egg to a nearby store where they were given 5-cents which they spent on candy.

One day he stumbled on the steps and dropped his egg, breaking it. However, the store owner saw what happened and allowed him a nickel’s worth of candy anyway.

Sharp’s father enjoyed spending a lot of time at his grandfather’s farm. His grandfather, George Wood, had a 150-acre farm located two miles east of Andersonville on both sides of the road where Big Valley Estates is now located.

One of the things he remembered was the big meals his grandmother cooked three times a day on a wood stove. They ate cornbread, biscuits, country ham, squirrel, rabbit, and had plenty of garden raised vegetables.

Both of Sharp’s parents attended Andersonville Institute. That was a 12-grade private boarding school that was noted for its music program. It was located where Andersonville Elementary School now stands.

In fact, the bell in front of the elementary school came from a belfry in the Andersonville Institute belfry. For a time the school was owned and operated by the Clinton Baptist Association.

Sharp’s mother played on a high school basketball team that went to the regional championships. At that tournament the basketball coach from Lincoln Memorial University saw his mother play and offered her a basketball scholarship.

The family sold a calf for $35 and the proceeds were used to buy a suitcase. Sharp’s mother and her sister packed their clothes together in that one suitcase to go to college. Most of the students at Lincoln Memorial University worked at various jobs on campus for 20-cents an hour to help pay their tuition.

Sharp’s father went to Carson Newman University at a cost of $400 a year and became a school teacher. In the summers, between school sessions, he worked on Norris Dam. He taught for 45 years. Some of his time teaching was a great experience and then there were other times when he would liked to have been able to walk out the door and not come back.

The first three years were spent at Braden Flat, a one room mountain school. He was paid $80 a month and his duties including being the school’s janitor. He paid Andrew Braden $4 a month for room and board.

If the mountain people liked you they were good to you. If they did not like you they ran you off. Evidently the mountain people like Sharp’s father. One day he mentioned making an outdoor basketball court. The people asked what it would take to build one. The next day they showed up with the necessary material to build a basketball court.

The remaining 42 years of Sharp’s father’s career were spent at Andersonville where he also served as basketball coach. Of those 42 years he was principal for 40.

When Sharp’s father was a young man there were very few cars. The roads were one lane and approaching cars or wagons had to each move to their side of the road to pass.

A trip to Clinton involved crossing the Clinch River on a ferry, as there was no bridge. There was bus service to Knoxville with two trips a day.

In the early years of the 20th century, even though there was no electric service in Andersonville, the people were served by a telephone company called The People’s Telephone Service with a switchboard and party line telephones.

Sharp’s father said many people could not afford the $1 a month charged by the telephone company, so the company went out of business and then there was no telephone service in Andersonville for several years.

One of the most interesting features of the journals is a map of Andersonville in the period 1912-15 drawn from memory by Sharp’s father.

More than 30 buildings were identified including dwellings houses with names of the owners.

Some of the buildings depicted on the map are still standing. In addition to the Baptist church, there were two Methodist Churches, one affiliated with the northern Methodist denomination and the other affiliated with the southern Methodist denomination. There was a grist mill, a shoe shop, a blacksmith shop, a post office, a planer mill and five stores, one of which sold caskets.